X-Men Retrospective #1 – Pre-Phoenix

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); The X-Men have held a significant place in my heart for a large portion of my life. While I have vague recollections of the pure, undistilled awesome of the 90's X-men cartoon, it was really X-Men

The X-Men have held a significant place in my heart for a large portion of my life. While I have vague recollections of the pure, undistilled awesome of the 90’s X-men cartoon, it was really X-Men Evolution, the Kids WB cartoon series, that truly introduced me to not only the franchise, but superheroes and the idea of comic books. It had become important to me, and I wound up passionately discussing things like Magneto’s morality, Nightcrawler’s parentage, and the specific mechanics of Cyclops or Rogue’s powers with anybody who was also a fan. It was around the time of the first two X-Men films, both of which are great. With X-Men: The Last Stand in 2006, I found myself less invested in the series, which makes sense. That movie was garbage. Luckily it was the X-Men that hooked me back into the franchise, and ultimately created a comic book fan. While pouring through Wikipedia page upon page of Marvel lore around 2009, I stumbled upon an X-Men story called House of M, which fascinated me, and made me an X-Men reader.

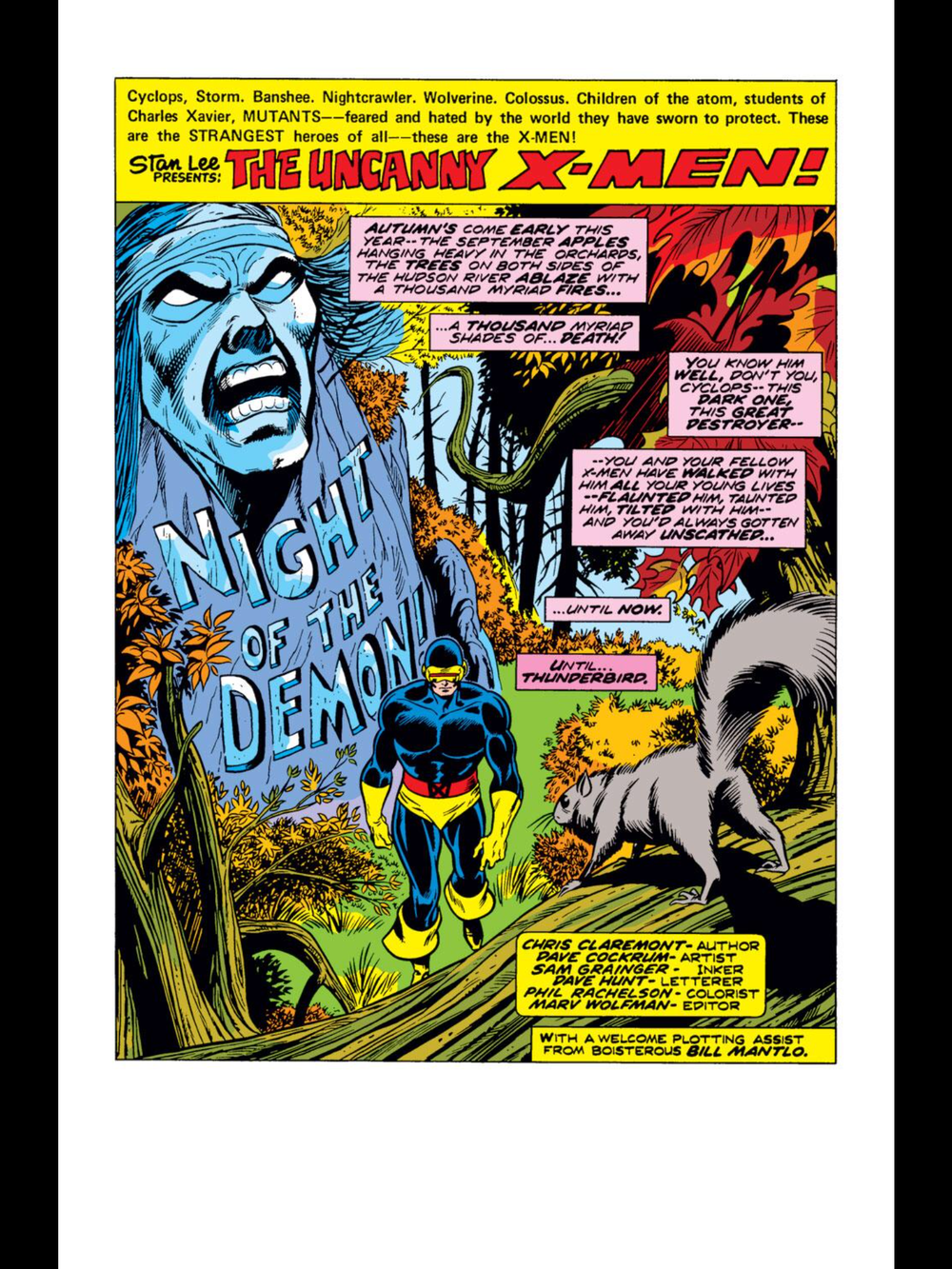

When it comes to retro comics, and specifically comics of the 1980’s, Frank Miller and Alan Moore. They have no doubt earned their places among the pantheon of comic creators, but it does a disservice that people do not mention Chris Claremont as readily. Claremont got his hands on the X-Men in 1975, when it wasn’t selling terribly well and had been reprinting older stories with new numbers (think of these as comic book re-runs). He wrote Uncanny X-Men and the majority of spinoff series until 1991. Let that sink in. From 1975 to 1991, the primary X-Men book and the spinoffs were the written by one person. That 16-year, multiple-title run creates what is potentially the greatest serialized epic of modern times. He elevated characterization to a level that comic books hadn’t seen, plotted so intricately that he often foreshadowed years ahead of where continuity currently was, and elevated a failing series to become the most popular series Marvel had.

So what are we doing here? Simple. Every single X-Men story if the 1980’s was a Chris Claremont story. But that story begins in 1975. This epic breaks down into a few epics. Some are very famous, and I can’t wait to tell you about the Dark Phoenix Sage or the Brood Saga, but this article is about what I am going to call the Pre-Phoenix Saga. This spans six issues, from Giant Sized X-Men #1 to Uncanny X-Men #100. These are, for the most part, monster of the week stories, but they’re significant in the sense that they establish the major players of this X-Men team (Cyclops, Wolverine, Storm, Colossus, Nightcrawler, Banshee, briefly Thunderbird, and eventually Jean Grey), establish key elements of the world these characters inhabit and how it responds to mutants, and includes two major plot elements that have consequences that span the entire series.

Chris Claremont is a wordy writer. There is no way around that. If you are purely accustomed to modern comic storytelling and the couple of dialogue-free pages that it can sometimes entail, you will find this change a little jarring at first. Stan Lee can be accused of the same thing with literally any Silver Age comic, but unlike Lee, every word that Claremont uses is significant in some way. Everything advances the plot, develops character, or establishes mood. If you sat down with a TPD like New Avengers Vol. 1 or House of M, it is reasonable to think that you could casually knock out all 6 – 8 issues contained within the time of a short nap. While you could read six issues of early Claremont in one sitting, I don’t exactly recommend it. It takes time to break apart certain elements, and more noticeably it can wear you down. Don’t let this be any indication of quality; it is just different from what you may be used to.

While the opening arc of Claremont’s X-Men doesn’t introduce the mutant hunting Sentinel robots, his vision of their implementation makes them seem like a larger threat, and makes the world seem much more anti-mutant than anything during the Silver Age. Claremont’s Sentinels are funded by the government in shady, backdoor ways, and are disguised to look like the original X-Men team. When the X-Sentinels fight the new X-Men, the X-Men get beaten. Claremont from the start avoids the problem of invulnerability in superhero comics. The way that the Sentinels are used makes the prejudices of the world of X-Men feel utterly pervasive. It is the first time that it truly feels like the heroes are fighting for a world that hates and fears them. It feels believable that this present can lead to the horrors of the Days of Futures Past timeline, which I can’t wait to dive into. Part of why the X-Men have remained so culturally relevant is because of their status as the oppressed. The mutants stand in for the civil rights movement or the struggle of the LGBTQ community at different times. The analogy doesn’t always hold up, but for most of Claremont’s run it works powerfully. It blooms in God Loves, Man Kills, but these opening comics really sow the seeds for that. In the current post-Trump campaign American landscape, we need the X-Men, but that’s really an article for another day.

One of the most striking things about the Pre-Phoenix arc is most noticeable when you look at it in the context of comic books as a whole. Two things happen in these six issues that has repercussions still felt in modern X-Men. If you don’t want to be spoiled for the plot of these issues, consider yourself warned. Claremont always believed that nobody should be an X-Man forever, and that people should grow up and leave the team. The other way for them to be removed from the team is by dying. Two X-Men die in these opening comics. The first is Thunderbird. While he doesn’t wind up being as relevant in later issues, his death really propels and sets in motion a lot of early development of the team. The second is Jean Grey. Her death is a self-sacrifice to protect her friends from a solar flare while re-entering Earth’s atmosphere. I would go into further detail now, but this is only the Pre-Phoenix Saga. The Phoenix and Dark Phoenix arcs are where this is going to ultimately come to a climax.

If you would like to learn more about the X-Men from this era, I strongly recommend the podcast Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men. If you would like to read these stories, you can find them collected in a variety of forms or digitally on Marvel Unlimited.

http://www.xplainthexmen.com/category/podcasts/