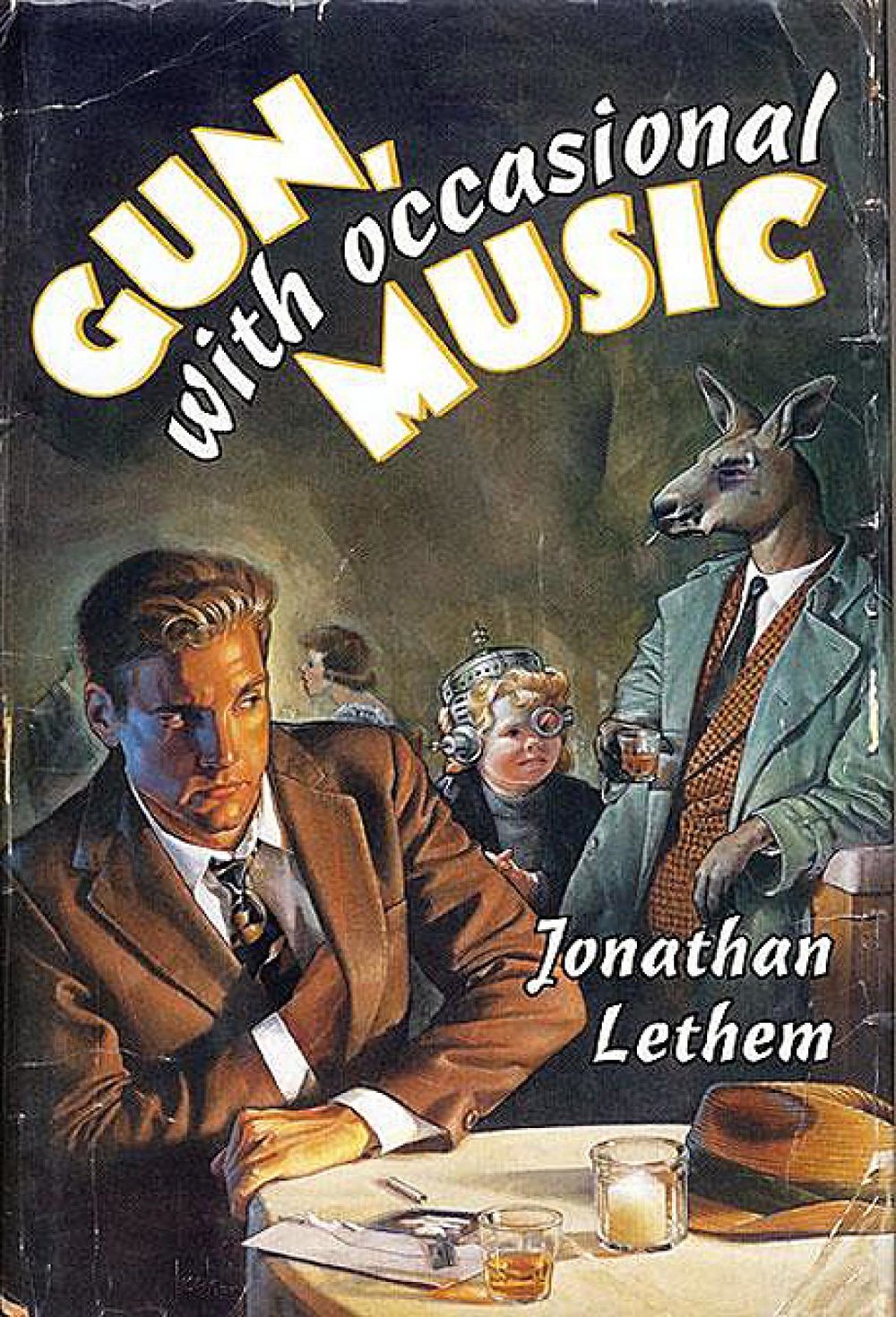

Gun, with Occasional Music – Jonathan Lethem (1994)

The following text is a result of taking a deliberate plunge into absorbing waters of the Gun, with Occasional Music River. As one may suspect, the word “deliberate” suggests that the book I have recently decided to tame – this time not only with eyes

The following text is a result of taking a deliberate plunge into absorbing waters of the Gun, with Occasional Music River. As one may suspect, the word “deliberate” suggests that the book I have recently decided to tame – this time not only with eyes full of deliberation but also with a reservoir of letters and sentences – should definitely be labelled with a touch of chipped linguistic playfulness as “The liberation from choice”, traceable at least in three tributaries which could be found in the novel’s catchment: the reader, the protagonist’s reality and the whole text itself. The first one was sourced from a grasping blend of baby blue runs of narrative’s lightness and turquoise rapids of flawless generic duality: hardboiled detective fiction and Philip K. Dick’s soft sci-fi influences, all of which are nothing but dashing appearances of the third tributary itself. In other words, the waters which had evaporated with all the possible and impossible reflections and gleams from the main stem of Jonathan Lethem’s debut novel, replenished the spring of my little brook and carved its mouth in the shape of the ensuing text. But what about the second tributary? What does it actually look like and how does it affect the remaining two?

Set in an undisclosed future, Gun, with Occasional Music tells a story of Conrad Metcalf, a worn-out, smart-mouthed private inquisitor in his early forties, who is always very fond of snorting one too many of his favorite make lines to get things going as well as throwing in cheeky, one-line metaphors and retorts while talking with someone, especially women and shady-looking individuals. Metcalf strongly resembles a future incarnation of Raymond Chandler’s best-known character – Philip Marlowe – however the former is enriched by some postmodern ‘uncertainties’. For instance, one day our ‘private inquisi-dick’ exchanged nerve endings of his genital area with his then girlfriend in order to broaden their sexual experiences. Unfortunately, his other half fled unexpectedly, leaving his privates still very private and fully operational (as the flesh without nerves can only be), although totally devoid of an ability to provide him with male sexual sensations. Having been shattered by the dismantling sex swap, Metcalf took a self-imposed vow of celibacy and decided to fool around with drugs instead, only to find himself ridden with an inflamed misogynistic resentment and a general rudeness of his character which has been counterbalanced by a strangely twisted persistence and an inner inclination to help lost souls get back on their feet.

Even though the protagonist’s sophisticated existence might evoke images of skillfully crafted characters from many other novels, it is only the world we are witnessing through Lethem’s first-person narrative that leaves us with nothing but the necessity to bow to the mastery of its construction. The author – using linguistic concision or even condensation which, on the other hand, should never be regarded as deprived of an articulate yet pleasantly rough-edged flow – depicts a dystopian reality with children turned into so-called “babyheads” – a gloomy result of some universally implemented intelligence enhancement therapy, the very same which made all the animals stand upright, use language and behave like people in general. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. The whole society is alienated so extensively and intensively that asking about somebody’s personal life is considered a sign of outrageous impoliteness (each case is therefore an exceptionally tough nut to crack for every private inquisitor, provided they are hired by anyone at all), the printed word is prohibited (Metcalf is watching “Oakland Photographic”) and psychology has been downgraded from science to itinerant, proselytizing religion. Not to mention the fact that almost everybody is addicted to legally sold drugs which alter human psychosomatic balance on purpose (for example, if you snort a few lines of forgettol, you can kiss your short and long-term memory goodbye for the rest of the evening). Karma points also play a crucial role in everyday life, being an official indicator of resourcefulness as well as justification for continuity of individual’s existence (if your karma level drops to zero, you are sentenced to hibernation). Astonishingly, all of these civilizational ‘marvels’ are fused with the rest of the hard-boiled features so naturally that it is almost impossible to perceive them as something disturbingly bizarre at all. Lethem’s writing skills are on a par with Dick’s ability to merge even the most ridiculous elements and concepts with the background reality. He strips their strangeness away and leaves them covered only in a thin layer of ‘invisible normality’, the trait expressed, for instance, by intelligent coin-operated household appliances and doors in Ubik which threaten to commence legal proceedings against every individual stupid enough to use them improperly or hack their CPU’s.

Focusing attention on this ‘unintentional’ world which is, in my humble opinion, far from wearing a badge of symbolic critique of contemporary times (however, it is getting harder to defend the above statement after reading the second part of Gun…), there can be traced one deliberate aspect of it after all. “The liberation from choice”, mentioned in the first paragraph, an idea which neither serves as an example to construct a thorough (or lightweight) assessment of the present-day condition of mankind nor possesses the ability to prove, envision or justify anything. It is more like an abutment which is hatching its bridges – spanning the third tributary in many unrecognizable dimensions – and lurking somewhere between (or rather ‘behind’) the lines of protagonist’s reality like some mysterious specter, dressed in a delicate unobtrusive conceptual superficiality. When we are co-investigating the murder case along with Metcalf, it suddenly overflows us and we know that we – as readers – ‘overflow’ it too. And our stream beds are beginning to convert into the unavoidable, the necessity of words and sentences to simply be written down…

My little brook formed an estuary in the shape of this review. It had no choice – it was liberated by reaching a confluence of itself and inevitable meanders of the Gun, with Occasional Music River, bristled with an infinite number of bridges like a non-existent mythical hedgehog or a porcupine made out of three elements – water, concrete and steel – which are not what they seem. What would your and Jonathan Lethem’s confluence look like?

Amonne Purity