John Carpenter: Dark Myth Weaver of the 1980s

Many of John Carpenter’s films have common threads that stitch them gently together. For instance, the majority of the visuals (camerawork, exposures, etc.) create a mood that is not only nightmarishly dark but also thrown into stark, bold contrast. It creates the effect of a

Ever since my early preteen VHS-rental forays into horror and dark sci-fi cinema, I have been a big fan of the work of John Carpenter. In particular, I have always felt that his work during the 1980s was perhaps his best; I mark his era of best work with the bookends of 1980’s The Fog and 1988’s They Live. During this time, Carpenter had discovered and perfected a style that REALLY worked for him, and it was undoubtedly effective, as it created a set of films that are still legendary today.

Many of John Carpenter’s films have common threads that stitch them gently together. For instance, the majority of the visuals (camerawork, exposures, etc.) create a mood that is not only nightmarishly dark but also thrown into stark, bold contrast. It creates the effect of a spooky slap in the face. Carpenter is also known for scoring many of his own movies, and doing a superb job of it. JC himself has said that this has much to do with the influence of his father, a musician and music teacher. Carpenter’s score work is undoubtedly both familiar and influencing in its own right, especially among many of our readers and featured artists. Carpenter took synth music to a gloomy, ominous place, and in his darker films, the synthesizer is as much his paintbrush as the camera or the actors.

I’d like to touch briefly on JC’s work previous to the timeframe mentioned; it is not without merit, and in fact includes the original Halloween (1978) and Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), both of which are incredible films. To be fair, it is perhaps in 1978’s Halloween that we see the initial jelling of Carpenter’s masterwork elements. A pervasive darkness hangs over both films, and both are deeply evocative of the feelings they reach for within the viewer.

While I wasn’t as sucked into The Fog (1980) as I was into some of JC’s other movies, it is still a dim, gruesome film worth any horror fan’s time. One notable thing about John Carpenter’s work during this decade is his preference for a certain set of actors and actresses; in The Fog we see Adrienne Barbeau and Tom Atkins amongst the people combating the menace of mist-shrouded maritime undead. Both would be used again by Carpenter in later films, and in fact both appear in his very next full-length film mentioned below. Notable also is Carpenter’s work on the soundtrack. While it isn’t the first film of his that he scored, it sets the tone for later work.

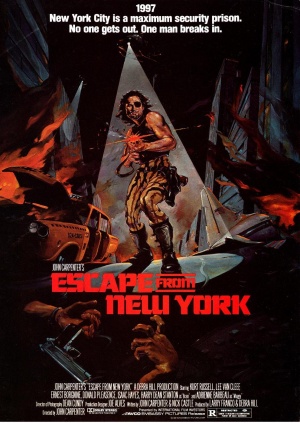

However, my initial jump into Carpenter’s work came with one film in particular… 1981’s Escape From New York, perhaps my favorite of JC’s, and easily near the top of my personal Top Ten list for films, period. Carpenter scores this work as masterfully as he directs it; the main title music is iconic, and undeniably cool as hell. Also worth mention is the music during the first scene where we see The Duke’s posse drive up to Brain’s hideout. It’s very catchy, and tells of JC’s own influences. For lack of more flowery words, the soundtrack just seems to fit. So does the visual setup for the film, which was actually filmed in East St. Louis, not New York City. So engrossing and attention-absorbing is the film that only by pulling yourself all the way out of it can you notice the little things that mark it as a movie and not somehow real.

In this film, Carpenter and crew paint a drab picture of a dismal (then) future, with the Cold War still raging and Manhattan converted into a vast prison-island meant to contain all of our nation’s worst criminals. The President’s plane crashes into this very wasteland, jeopardizing him and America, and perhaps even the world. Enter one of cinema’s most badass antiheroes ever, Snake Plissken (played by Kurt Russell).

Escape From New York sets the tone for a lot of John Carpenter’s work during this era; it explores themes of bleakness and cold terror within hyperbolic situations that are just real and feasible enough to amplify those feelings. The story is an anthem about man’s inhumanity to man, on several levels, and even the ending isn’t your typical “all loose ends tied up” cinema finish – but it is still satisfying and ultimately effective. It was both a commercial success AND an eventual cult classic, whereas most films of this “adventurous” type are often lucky to be one or the other.

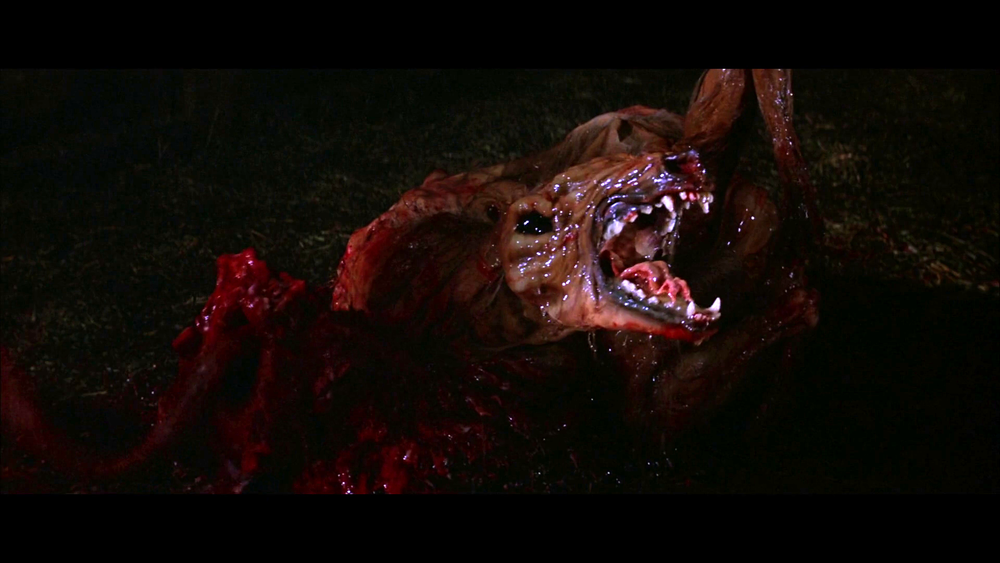

Next comes 1982’s The Thing, based off the story “Who Goes There.” Kurt Russell is back, this time as a helicopter pilot trapped in Antarctica with several of his co-workers at a research outpost… as well as a terrifying, shapeshifting predator from beyond the stars. This film is notable within the context of John Carpenter’s broader work for two reasons: it is the first film in what he calls his “Apocalypse Trilogy” (the other two are Prince of Darkness and 1994’s In The Mouth of Madness), and it is one of his films he didn’t do the score for. That job went to well-known spaghetti-western soundtrack artist Ennio Morricone, who chose to create a fittingly ominous, minimalist score. While it’s no comparison to Carpenter’s own score work, it does its job adequately. Themes of paranoia and isolation run rampant, and again, you won’t be seeing many bright colors or happy endings. Rob Bottin headed up FX for The Thing, and his work is still praised for its sheer visceral quality. It was no easy task to depict the titular Thing’s various forms and transformations, and yet it is done so convincingly in this film that the FX work is still considered a benchmark for most FX artists.

In ’83 and ’84, Carpenter headed up Christine and Starman, respectively. Christine is an adaptation of the Stephen King tale of the same name, a story about a desperately uncool young man who finds the cherriest ride… complete with a possessing spirit that compels both him and the car to kill. Starman, honestly my personal least favorite from this era of JC’s films, is a story about an alien entity taking the form of a woman’s dead husband (Jeff Bridges) to take the woman on a magical journey, with G-men on their heels.

In Christine, the source material is followed fairly faithfully, with only the usual “come on, Steve” bits of King’s original work altered or omitted. Actor Keith Gordon acquits himself admirably as Arnie Cunningham, the hapless bloke overtaken by the demonic set of wheels. While not overall as dark as the rest of this set of movies, Christine is nonetheless suitably grim and shadowy, both visually engaging and full of chills as boy and car become one and lash out at the world around them.

I’m going to lay this out really honestly for you folks: I didn’t care much for Starman at all, but that’s just my personal taste. It comes off as a weepy, ephemeral pseudo-romance, but contains soft sci-fi elements as a necessity of its makeup. It’s cool how they tie in the whole Voyager 1 golden record thing to the story, but the drippy cliché of a woman teaching an alien (in her husband’s body) what love is… I’m sorry, that’s too much for me. I’d say Starman is a good date movie, because it’s not badly done, it’s just definitely “softer” than Carpenter’s other films. However, even though it is slightly more of a “feel good” movie, it is still distinctively Carpenter: crisp, sharp visuals with plenty of contrast, a solid, busy storyline, and more than acceptable performances by the cast.

Big Trouble In Little China (1986) could also be called “light hearted,” at least parts of it… but it’s no soft story. Kurt Russell is back again, this time as rough-around-the-edges (yet surprisingly stylish) trucker Jack Burton. Burton and his pal Wang, along with bus driver/sorcerer Egg Shen (Victor Wong) get wrapped up In the business of an immortal villain, Lo Pan (James Hong) and ultimately thwart his plans to regain his youth at the expense of the beautiful young Gracie Law (Kim Cattrall) and Wang’s lovely bride-to-be.

Big Trouble In Little China has elements of horror; waterlogged rooms full of corpses, a slavering, shaggy monster, and lots of black magic. Ultimately, however, it is a comic-book like foray into over-the-top action and visually enchanting folk-fantasy. Victor Wong (who reappears in Prince of Darkness) and James Hong steal the show, both putting on fantastic performances as two magicians pitted against each other near the end of the film. Russell spits out tons of memorable quotes and one liners; to this day, when I head out of the house to do something even remotely risky, I say “if we’re not back by dawn, call the President.”

Prince Of Darkness (1987)… where to even begin with this one… it’s your classic “we have to stop the Devil from coming into the real world” story! Victor Wong is back, this time as a metaphysics professor whose team gets called in by a distraught priest (Donald Pleasance) to investigate a giant tub of hell-liquid. They discover the truth, which is that the apparatus is a conduit between our world and the extradimensional prison of the film’s titular villain, Satan himself. The team must then find some way to forestall or stop the inevitable release of Satan into our world, as it’s happening, in real time!

This film is the second in John Carpenter’s unofficial “Apocalypse Trilogy,” and belongs there. As the team continues its research, several of them get possessed by the liquid, murdered in horrible ways by those possessed, or simply scared sh*tless as all of this continues to snowball into Satan’s new birthday. One female member of the team becomes “pregnant” with something, and also her skin sloughs off.

The grainy, VHS-esque dream sequence from this film, and the pizza-face lady, haunted my subconscious for weeks after my initial exposure to the film, and still remain among the most solid horror visuals in my mental vaults. The soundtrack, again fairly minimalist, is nonetheless incredibly fitting, and the visual work is superb.

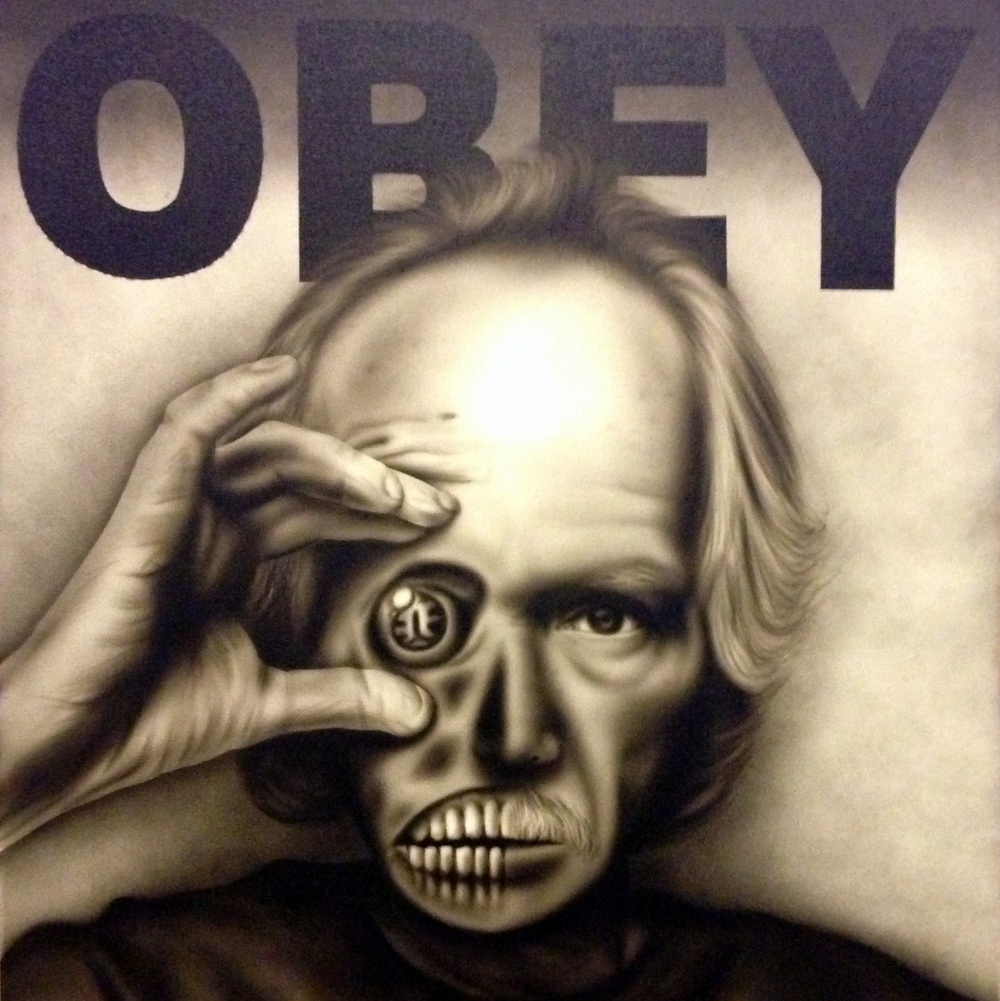

Finally, we come to another of the indelible stamps Carpenter made on 80s cinema: 1988’s They Live. This film is notable for its socio-political overtones and its telling analogy of our real life under the yoke of “the Man,” but to me it is also legendary because it stars pro wrestler and old-school ass-kicker Roddy Piper, who makes the film what it is every bit as much as Carpenter does by directing it. Piper plays the character named Nada (in the credits; he is never referred to by any name in the film), a drifter with a simple morality and a set of balls that must be diamond-plated. Keith David also stars, as well as Meg Foster and a number of other talented performers who see regular use in Carpenter’s films for good reason. I will let two video clips speak for me on the merits of this classic movie:

They Live depicts a hyperbole of the world as we know it (and as many suspect it). It is humorous in little pockets, thanks to both Piper and the script, but its overall tone is one of the common man’s desperation in the face of monolithic oppression and control. It has perhaps one of Carpenter’s “happier” endings, but I won’t spoil the ending here in case someone’s not seen it. I will say, however, that depending on what you believe about humanity and the world, the ending may even leave you oddly fired-up and inspired.

After this era, John Carpenter has continued to make films worth watching; notable among these are In The Mouth of Madness (1994) and Village of The Damned (1995). He has created other work that didn’t go over as well, such as 2001’s Ghosts of Mars, as well as films that are considered “just okay,” such as 1998’s Vampires. Nonetheless, though John Carpenter is most well-known as the creator of Michael Myers and the Halloween franchise, it is my personal heartfelt opinion that his best work is (and will always be) his 80s films.