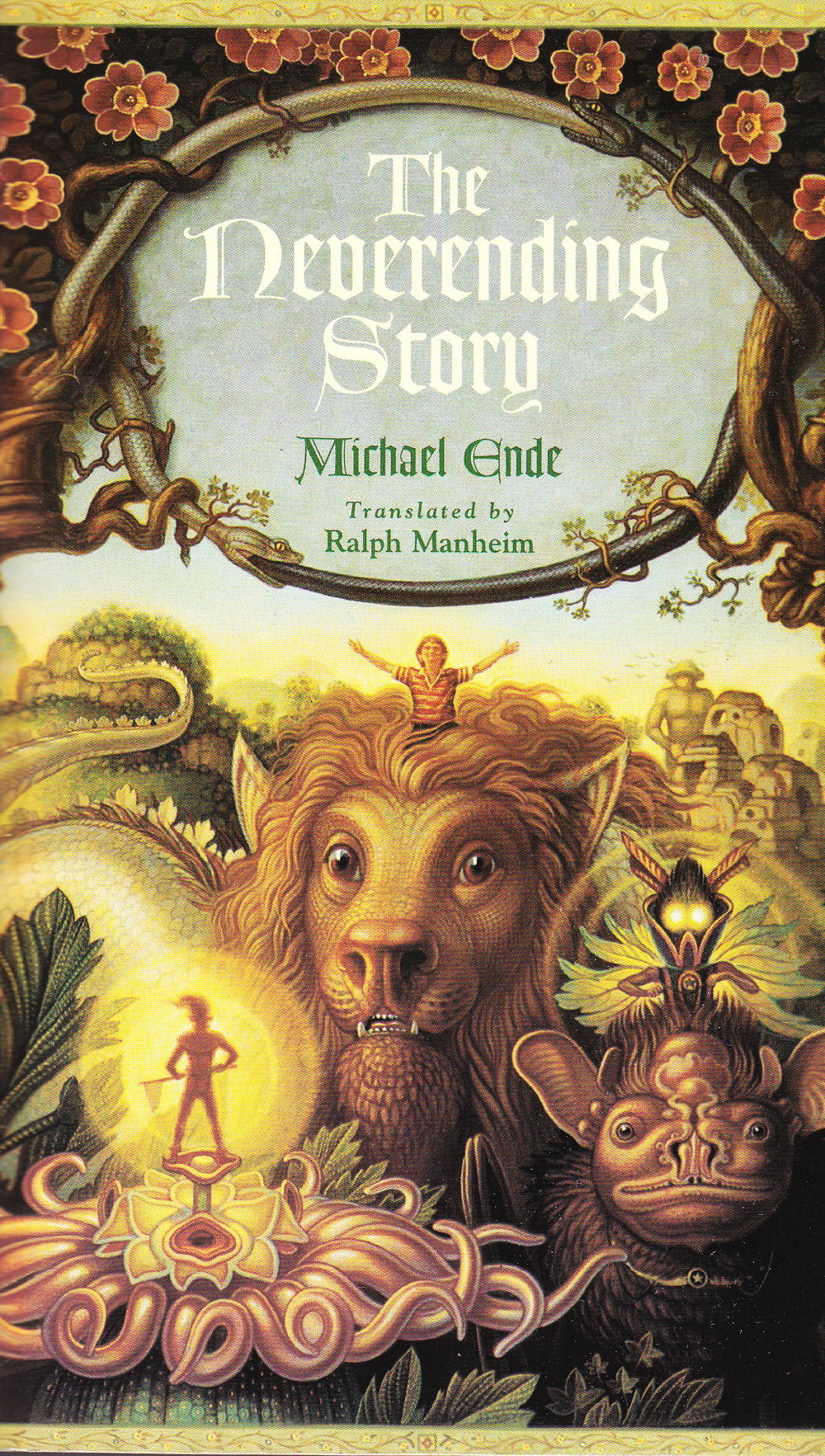

The Neverending Story – Michael Ende (1979, Tr. 1983)

Yet tell me, My Dear Platinum-eyed Reader, if it is conceivable for the never-ending divinity of letters to corrupt or get desecrated? And is it possible to forget the story which never ends?

“Profanity of words” – the phrase for today. Unnecessary sentences and paragraphs served as additives, which suddenly begin to host a curved hump of a “c” in the very center of their now addi-c-tive ‘vicinity’. All the letters scribbled about their next of kin eventually fall under this highly ambivalent category. These secondary, even tertiary mirages, echoes and aftershocks of something which has already been written, these passages made out of crumbling plaster, casted in a mold capable of enduring liquid wolfram, titanium and gold, seem to play many different roles, the most valuable ones being: highlighting, encouraging, popularizing, informing, simplifying, etc., but, unfortunately, every rose has its thorn – they can also: bore, outrage, disconcert, exaggerate, flaunt, and so on. On rare occasions (are they really that rare?), the sacrilege conveyed by the derivativeness of texts about texts hits the critical level. Ever since the speech and its penned down twin – the writing – have been held in silver esteem, the only solution applicable to their blasphemous superfluity was to repent and dip our pens in an ink of silence, which has always been thought of as golden in color (indeed, it is the most pregnant element of language to this day). But what would happen if we could get someplace via neither silence nor words, where we would not only break free from the chains of letters riveted to the hoary chestnut called Profanity, but also stimulate our imagination to synthesize genuinely trailblazing ‘platinum’, which would simultaneously retain the possibility to get desecrated, defiled, sullied, yes, but only in a positive manner? We would have to set out on a journey throughout Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story.

As much as children literature is considered a genre, which has often delivered portrayals of something from a domain of human life that exists and should exist (tightening knots of friendship, overcoming hardships, handling and reciprocating gratitude, etc.) by means of things which simply do not (unicorns, enchanted castles, powerful wizards and the like), as opposed to the traditional fiction, which has been focused more on creating stories about things in various ‘modes’ of existence (e.g. mysterious relations overlooked in the everyday hurly-burly, perplexing sensations, bewildering chains of events, ontologically unlikely characters, etc.) using ‘cogs and sprockets’ of a narrative exhibiting real, palpable, down-to-earth consistency – their blend, which a well-crafted attempt is The Neverending Story itself, may be perceived as a pretty unusual nexus. That is why Ende’s most renowned novel parades without any complexes among such seminal titles of prepubescent literature as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Winnie the Pooh and Peter and Wendy, although being much younger than its classic ‘siblings’. It also would not look immature, if we shelved it next to some C. S. Lewis’ novels or J. D. Salinger’s short stories. Nevertheless, the splendor of strut undoubtedly overshadows the maturity of presence. So what distinguishes The Neverending Story from its ‘underage’ peers, then?

A hunch is whispering in my ear a plausible prompt that the certain ‘area of expressions’ undertaken by German author is what stands out here the most. Alice’s wonderful exposure to and exposition of linguistic, temporal and spatial playfulness, Pooh’s delightful silliness and Peter’s adventurous raucousness can be counterpointed with Ende’s genuine inclination towards literature and all the multi-dimensionality it denominates, a longing for an endless escape to infinity or maybe for an infinite escape to endlessness and a deep allegory about growing (not necessarily up), going astray and being saved by self-redemption (with a little help from kind friends). All of this is seasoned by an absolutely unpretentious, almost hidden morals we are obliged to crystalize on our own and a quintessential flavor every solid fiction should be saturated with – the sweetness of sheer magic.

The novel tells a story of Bastian Balthazar Bux, a bowlegged, chubby, rather clumsy, somewhat disillusioned, often neglected by his widowed father and definitely bullied by school hoodlums ten-year-old boy, who, under the it-just-turned-out-this-way circumstances, steals a novel entitled “The Neverending Story” from an antiquarian bookshop owned by a man called Carl Conrad Coreander. Being pricked by his conscience and ridden with a feeling he has nobody to turn to and nowhere to go, Bastian decides to lock himself up on the school attic, where he can read his randomly obtained loot. However, after several chapters, our little avid reader, name ‘generator’ and storyteller (his only irrefutable skills and virtues) finds out that The Neverending Story is not just another ordinary story, which could be stolen from a second-hand bookstore, and experiences first-hand even more than literally, what it means to be totally gripped by and get into the plot…

Perhaps the wisest way to describe the referentiality, the ‘texture’ of motifs and the interconnected meta-level composition of The Neverending Story would be to draw several in-depth comparisons with other texts of juvenile literature, which are extraordinarily prone to the above type of evaluation, mainly due to the axiological charge running through their ‘wiring’. Regrettably, or quite the contrary – without the slightest trace of remorse, I have been drugged by the vision of the ‘platinum’, towards which Ende’s opus magnum is paving way for all the letter profaners and future ‘sentencary’ saints out there. Besides, the book prevents us from judging it in the matter-of-fact assessment mode in the first place, because it has been dosed with the intensity of a full-blooded adult fiction, which tends to fluctuate, multiply and double-cross. We often forget that our protagonist or, shall I say, “protagonists” – for there is another youngster, Bastian’s ‘neverending’ anti-doppelgänger Atreyu (the prefix “anti-” taken very flexibly here) – are preteen fellas, especially when we are witnessing Bux’s metaphysically brilliant conversations with Grograman A.K.A. The Many-Colored Death or his Sisyphean task at the Minroud Mine. On the other hand, Atreyu does not fall behind with his spine-tingling confrontation with a dying werewolf Gmork in Spook City, surrounded by the oncoming Nothing. Their dialog, pumped up with a thinly camouflaged critique of an extensively sprawled ‘short-sightedness’ of our contemporary times (I should have used the term “blindness”, however I side with Atreyu, Bastian and Ende who all think, I presume, that the hope-crushing proposition “Life is like that” is a load of gibberish), makes you shed a tear with a platinum gleam inside. Or is it just a will-o’ the-wispy reflection of a marvelous filigree from the Silver City of Amarganth?

Reflections, ponderings, ruminations – another ‘nook’ of the book; this one reserved for adults and younglings, whose ‘juvenile’ eyes have been already blessed with a platinum insight and ‘outsight’ – form a gallery of thoughts, many of them tuning us in to amusingly speculative frequencies, not to mention lumps in our throats we are struggling to gulp thanks to their humane honesty. Some of our meditations are induced by frame tale narratives, varying from a single paragraph to a regular account, which have been studded throughout the whole book. A memorable example is Bastian’s tale “The Story of the Library of Amarganth”, which leaves us contemplating creative powers of the nomenclature or – if I may meta-wink a little at language myself – ‘the imagery of coinagery’ (when we invent a phrase, is it only a word or is there something more, ‘lurking’ behind this freshly concocted term? If there is something ‘out there’, what is it then? What could it be? Has it been there before? What is the ‘feeling’ of a difference between making up a portmanteau and forming an expression consisting of randomly picked letters? – these questions are only a warm-up, believe me!). Other notions, which are conjured up by the ‘choke-uppers’, the first-class tear jerkers (like Bastian’s stay in the House of Change with Dame Eyola), treat our hearts and souls as musical instruments, on which they play a slow jazz standard that resonates with the most fragile ‘strings’ of ours, which, for a well-known or a well-unknown reason, have been kept hidden, forgotten, ignored, mistrusted. Upon hearing their gentle weeps, we crack as easily as dreams from Minroud Mine. And then we cry as bitterly as Acharis, the ugliest creatures in Fantastica. It is during those moments that our eyes leach away platinum filaments, which forecast fantastic filigrees of forthcoming fonts and firmaments…

I know what all of you may be asking yourselves right now – what is this ‘platinum’ I have been obscurely (or even obtusely) hinting at all along? I am not sure. It may be something as straightforward (but absolutely not trivial!) as a feeling of being boosted by ultimate possibilities, whose unquenchable, child-like energy might still be attainable for everyone, despite the annihilating presence of Nothing. Or it could be something more complicated. For example our sincerest astonishment because we have found something unexpectedly cathartic in a totally unforeseeable place let alone ‘something’ from beyond the inexpressibility, which keeps hovering over neither silver platters of writing nor golden nuggets of silence. Or maybe it is, after all, only an addictive additive, a mirage, an echo, an aftershock of unnecessary letters, which give birth to nothing but a profanity (like the overzealously wordy one you have just read?). Yet tell me, My Dear Platinum-eyed Reader, if it is conceivable for the never-ending divinity of letters to corrupt or get desecrated? And is it possible to forget the story which never ends? I can already sense the shine of your platinum smile…

Amonne Purity