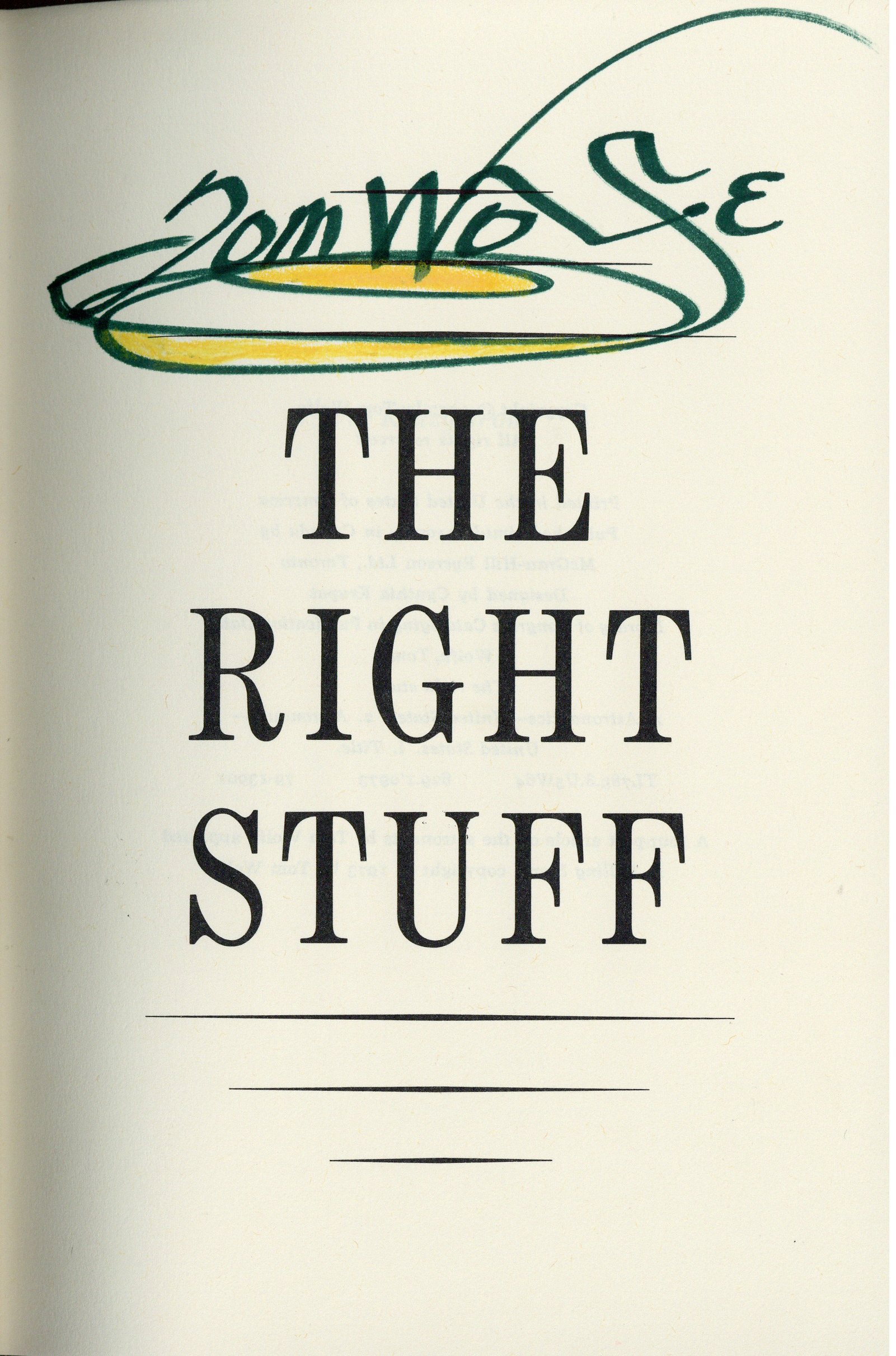

The Right Stuff by Tom Wolfe (1979)

With the successful release of the film Hidden Figures and being that it’s the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 1 launch disaster, I figured that I’d start 2017 with a switch to non-fiction.

With the successful release of the film Hidden Figures and being that it’s the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 1 launch disaster, I figured that I’d start 2017 with a switch to non-fiction, focusing on the critically acclaimed The Right Stuff by the New Journalism pioneer and provocateur Tom Wolfe. When the book was released in 1979, America’s self-confidence was at a nadir. The Watergate scandal and resignation of the president in 1974 shook people’s confidence in many of the country’s institutions; the country had retreated from Vietnam in 1975; and stagflation and the oil shortage were ravaging the economy. The book however takes a spotlight to a more optimistic time when the space race between the country and the Soviet Union caught the world’s imagination. The narrative, stretching from the end of the Korean War to the end of the Mercury program, reveals the trials and the triumphs of the U.S space program.

What is “the right stuff” that Wolfe speaks of throughout the book? The candidates for the Mercury missions are fighter pilots picked from various branches of the military. These are men with a devil-may-care attitude, with the exception of the late “boy scout poster boy” John Glenn, who is both idolized and teased by his fellow astronauts. They drive fast and fly dangerously, seeking new thrills while trying to maintain and improve their standing in the military. “The right stuff” is the physical and mental courage and resilience needed to not screw up when performing their duties, whether in the military, or later in the space program. Those who don’t have “the right stuff” flame out, likely harming their career prospects in the process. Even when the candidates are narrowed down and selected for the sub-orbital and orbital flights that entail the Mercury missions, will their mettle allow them to keep this resilience as they embark to places where only a few Russians have gone before? Even though it’s non-fiction, the book, just like a novel, tries to keep the reader excited for what happens next, as the astronauts’ varied personalities clash with each other and affect their dealings with the outside world.

Wolfe’s narrative shows that space program wasn’t all fireworks and ticker-tape parades, although it included these, especially after a successful mission. It was messy, political, and a bureaucratic nightmare. In the early years of space exploration research, there was even some controversy over even the status of NASA. Initially, the space program was an extension of the military branches, particularly of the U.S. Air Force. Then it went under civilian control. However, military officers are the men fed into the program. And still there are national security concerns. If the Soviets won the space race, would they be in a position to rain nuclear bombs down on the U.S. and their allies? What if they established a base on the moon? Vice-President Lyndon Johnson states that “he doesn’t want to go to bed underneath a communist moon.” And neither does the rest of the country. So, the Kennedy administration declares in what could be called his unofficial redo of his inaugural address the goal of sending a man to land on the moon by the end of the 1960s. As history shows, this was accomplished, though Kennedy himself did not live to see it.

Though the descriptions of the launches, flights, and returns are interesting, especially in their most harrowing moments, some of the most illuminating incidents in the book revolve around the background stories: the astronauts’ families, sudden celebrity, and the eclipsing of fame of previous astronauts when new achievements are celebrated. The astronauts’ families are supposed to shine out before the media lens as examples of the perfect middle-class household. But they are human like the rest of us, and occasionally, the cracks and flaws are exhibited to the world, often to the government’s chagrin. A notable example involves the wife of John Glenn, Annie. She had a severe stutter for the majority of her life. Unfortunately for her, the media wanted to get insights from the astronauts’ wives, especially immediately prior and during their husbands’ launches into orbit. During John’s launch sequence, there were some worries about potential issues, which lead to a media firestorm. It didn’t help that Lyndon Johnson wanted to insert himself into the situation as a potential comforter to Annie. However, she wouldn’t step outside to face the cameras, nor would she allow the vice-president inside her home to schmooze for the media outlets. The only person she was comfortable with was her and John’s assigned reporter for Life. John knew that his wife had extreme reticence speaking before an audience with that stammer of hers. So, he makes a firm stand explaining that if his wife is uncomfortable, she doesn’t have to be interviewed, even by Johnson. This flusters the media and leaves Johnson fuming over being shut down. Pondering the narrative, one can just imagine the expressions on their faces.

In 2017, the Soviet Union has broken up, there is an international space station where nations cooperate with other, and much of current space exploration is being funded by private enterprises. There have been great changes since the apex of the space race in the 1960s. However, to see where the future of space exploration can take us, it’s good to look back at the past, especially at the mistakes, to see what needs to be corrected. However, it’s also beneficial to look at the achievements. These men of the Mercury program were pioneers of what is now, though much is now diminished in certain areas. They were not scientists, but as they advanced through the program they had to perform their given tasks like scientists while maintaining the critical edge of “the right stuff” typical of brash fighter pilots. Some ended up paying with their lives, like Gus Grissom, who perished with two other astronauts during the launch sequence of Apollo 1. Others, such as John Glenn, lived fulfilling public and private lives long after they qualified to blast off into orbit and beyond. But all these space warriors had heart and “the right stuff.” That’s something to cheer.